what is the name of eakins painting that is similar to the gross clinic? in what ways is it similar?

All to form the Hand of the mind;–to instruct united states that "practiced thoughts are no improve than good dreams, unless they be executed!"

–Ralph Waldo Emerson

Mind is primarily a verb.

–John Dewey, Art equally Experience

Thomas Eakins,

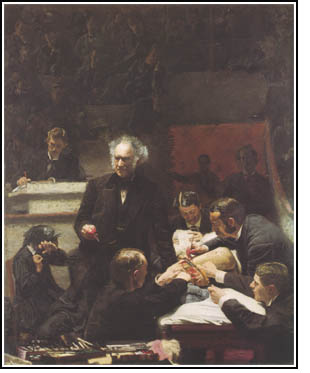

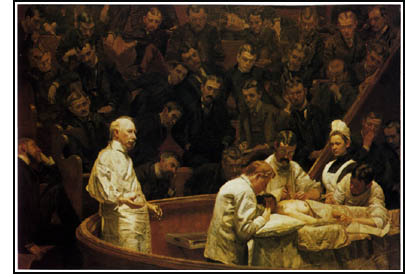

The Gross Clinic and The Agnew Clinic

Click here for all-time press of text

"Forming the manus of the listen" is an ideal in Emerson, a set of philosophical insights and procedures in James, and a literal depiction in dozens of Eakins' paintings. Few artists have more securely explored the relation of thought and execution. For a quick introduction ane need only glance at ii of Eakins' best known works: The Gross Clinic and The Agnew Clinic. They clearly take the relation of hand and mind as their subject.

"Forming the manus of the listen" is an ideal in Emerson, a set of philosophical insights and procedures in James, and a literal depiction in dozens of Eakins' paintings. Few artists have more securely explored the relation of thought and execution. For a quick introduction ane need only glance at ii of Eakins' best known works: The Gross Clinic and The Agnew Clinic. They clearly take the relation of hand and mind as their subject.

Mind is vividly represented in both. Gross and Agnew are portrayed at moments of deep thoughtfulness. At the moment Eakins chooses to imagine, each professor of surgery has briefly paused in his operation (and his lecture) to ponder something. A variety of effects emphasize their thoughtfulness. In the first place, there is the presentation of the head. Each is placed against a darker background and lighted and then as prominently to display his high-domed forehead, furrowed brows, and deep-gear up optics. (Gross is more theatrically presented than Agnew, illuminated as he is past a single source of calorie-free which leaves half of his face dramatically shadowed and creates a semi-spiritualized aureole out of his calorie-free gray hair.) As he does in many other works, Eakins heightens the expressive issue of both heads by highly modeling them and placing them against backgrounds that are much "flatter" than they are (both in the sense of existence less three-dimensionally rendered and beingness painted with less oily, more thinned-down pigments).

The placement of the surgeons with respect to the operating tables contributes to our sense that, at the moment Eakins has called to represent, each of the men has momentarily taken a meditative step off to ane side of the heaving bounding main of activity around him. Each is marginalized by a spatial caesura (smaller for Gross and larger for Agnew), and pivoted slightly abroad from both the students he addresses and the operation he conducts. Insofar as both doctors are turned away from their assistants and their optics are averted from contact with anyone effectually them, it is impossible to read the figures of Gross and Agnew equally interacting socially or physically with anyone at the moment nosotros glimpse them. We are meant to read them as "thinking." Their visual positioning figures their imaginative position: a land of contemplative withdrawal or meditative separation from the welter of events.

Only it is critical to notice their states of withdrawal are only fractional; both doctors are all the same immersed in and engaged with a series of practical events. Afterward all, Eakins chooses to depict Gross and Agnew not in their studies as thinkers, merely very much at work as doers. As surgeons and teachers in the midst of an operation, surrounded by hordes of others with various claims on their attention, they are in the heart of the most circuitous course of actions imaginable. This is a world in which action counts as much as thought–or, to put information technology more than accurately, a world in which action can't be separated from thought.

I would argue that the point of both paintings is precisely the ways that Gross and Agnew bridge the realms of thinking and doing. Eakins brings the signal domicile to us through a series of contrasts in which the meaningful connection of the two realms–of existence with doing, of mental impulses to manual expressions–is flawed or absent in various ways. At that place are dozens of arms and hands visible (and invisible) in both paintings, and their sheer number and prominence depict our attention to them, merely 1 of the things we slowly realize is that at that place are but a few in which hand and mind are linked in a disciplined, productive relationship–one in which mind informs hand and hand informs mind with the same degree of subtlety that Eakins' own hand and listen obviously worked in concert when he painted his work. Consider the most important groups of easily and arms in the ii works:

I would argue that the point of both paintings is precisely the ways that Gross and Agnew bridge the realms of thinking and doing. Eakins brings the signal domicile to us through a series of contrasts in which the meaningful connection of the two realms–of existence with doing, of mental impulses to manual expressions–is flawed or absent in various ways. At that place are dozens of arms and hands visible (and invisible) in both paintings, and their sheer number and prominence depict our attention to them, merely 1 of the things we slowly realize is that at that place are but a few in which hand and mind are linked in a disciplined, productive relationship–one in which mind informs hand and hand informs mind with the same degree of subtlety that Eakins' own hand and listen obviously worked in concert when he painted his work. Consider the most important groups of easily and arms in the ii works:

- First, at that place are the students' hands and arms, almost all of which are slack and lacking any executive function, if they are not only absent-minded (virtually blatantly in the centrally positioned student in the Agnew painting, who cannot bother to remove his easily from his pockets to take notes).

- Then there are the easily and arms of the figures in the entranceways to each operating theater. One man in the Gross portrait uses his arm to lean against the wall; another lounges against the opposite wall with his arms downwards at his sides. The figure in the Agnew portrait uses his hand to shield his whisper. None of the three might be said to put his limbs to productive employ.

- Next, there are the partially or totally obscured hands and artillery of both patients, which represent a tertiary grade of slackness or inattentiveness, cut off from mental control and usefulness by the haze of anesthesia.

- Then there are the arms and hands of the patient'southward mother (if that is what she is) writhing in hurting in The Gross Clinic. (Several sketches survive documenting the intendance Eakins put into her depiction.) Her arms and easily contrast with those of both the students and the patients without being any more usefully employed. Her gestures are highly expressive, but completely undisciplined and uncontrolled.

- At the other expressive extreme, there are the artillery and hands of the recording secretarial assistant in the Gross portrait, and the arms and hands of the various surgical assistants in both paintings. They figure a unlike, but equally limited, human relationship of paw and mind. I might say that they are examples of beingness all hand. They are instances of masterful manual dexterity (the ability to restrain, to hypnotize, to cut, and to record), but they lack the capacity to make artistic decisions. They but follow Gross'due south and Agnew'south instructions.

In this whirl of compared and contrasted limbs and gestures, illustrating diverse forms and degrees of mental and manual disconnection or infacility, simply Agnew and Gross truly combine mindfulness and handiness. In fact, in terms of one of the tenets of the pragmatic view, I would argue that they demonstrate that in acts of supreme inventiveness the divergence betwixt the two realms disappears. They erase the stardom between transmission and mental dexterity, insofar as their scalpel-wielding hands are clearly energized and mobilized by their thoughts equally much equally their thoughts are disciplined and instructed by their practical performances.

The particular positions and gestures of both doctors express the blending of the realms. The verticality of their presentation tells the states that the doctors rise higher up the only executive functions of the horizontally displayed elements of the operating tables beside them–however without losing bear on with that realm of action. As they step aside to recall or brand a point in their lectures, both doctors significantly concur scalpels poised for imminent activeness; they are not only lecturing about surgery, but practicing surgeons still at work. (No other effigy is given a scalpel in either painting.) Gross is placed in an specially complex double position: even as he takes a half-footstep back and turns halfway to the side, he is shown continuing to lean on the operating tabular array, with his left arm and his hand touching it (or the patient), maintaining intimate practical contact with the work at hand.

The same bespeak is fabricated less conceptually and more than perceptually by the presentation of the group engaged in the functioning in the Gross portrait. Eakins organizes the visual infinite and then that, of all of the medical figures in the work, only Gross presents a coherent, conspicuously legible visual identity. In their merely manual functionality, the other figures around the operating table are all on the verge of dissolving into visual incoherence. The impression is all the more bright when the painting is viewed not in a page-size reproduction but in life. In Eakins' looming, larger-than-life sheet, it becomes extremely hard to decipher the sprawl of the figures on and around the operating tabular array (especially given the dark monochrome of the color scheme). Even in reduced-size reproduction, in that location is such a disruptive overlap of bodies and limbs (with the patient crisscrossed by a network of assistants' hands and arms) that information technology becomes hard to tell what limb belongs to what person, or where one torso ends and the next begins (an issue heightened through the use of severe foreshortening). Gross alone presents a unitary bodily and mental presence, beingness granted a clear and separate visual identity. That is to say, equally a blemish of paint, Gross organizes the visual spaces of his painting like to the style, as a dr., he organizes the surgical infinite. His visual composure and organization is a kind of metaphor for his psychological and functional composure and organization.

That is to say, the paintings are not merely theatrical in their amphitheater settings and lighting effects, but subscribe to what might be called a fundamentally theatrical conception of personal identity. Figures limited themselves not only (as in traditional portrait painting) through their clothing, posture, gestures, and facial expressions, simply past means of practical forms of action and interaction with others. They are defined not simply in terms of states of beingness (which might be said to be the expressive mode of most other portraits), but in their applied mastery of forms of doing. In Eakins' definition of who and what we are, consciousness is not a just personal, private, internal state, but is required to externalize itself in a concrete grade of action. The shift from the one definition of identity to the other might be called the pragmatic turn. We are, at to the lowest degree in large office, what we do. Nosotros are our hands as much as our minds. The matrimony of the realms is crucial to the meaning of both paintings. For Eakins and all pragmatists, mental activeness is not a time out from practical operation. Thought is not an alternative to activity or activity an alternative to thought (every bit in Ideal philosophy), but each is a continuation of the other. Gross'south and Agnew'southward unique achievement is to bridge the realms of thinking and doing. They masterfully inject heed into the globe.

When, in "What Pragmatism Means," James called for a philosophy that turns "towards concreteness and adequacy, towards facts, towards activeness and towards power," he might accept been describing not only the philosophical predilections of the sorts of sitters Eakins was interested in painting (many of whom are men known for their practical accomplishments), merely Eakins' own fact-imbued forms of delineation. With his use of photography, his studies of perspective (and frequent use of perspective grids in his sketches), his movement studies, and his involvement in science and engineering, Eakins was so devoted to concreteness and factuality that he laid himself open to frequent criticisms of what was said to exist his overly "scientific," "factual," or "literal" treatment of his subjects. Equally Frank Stella once wittily remarked, works of fine art are e'er at least to some extent "lifted off the ground, upwardly in the air," but Eakins' goal, like that of James, is to reestablish contact betwixt ideals and practical realities.

It is not at all uncommon for artists to choose men of activity and practical achievement as their subjects, just what distinguishes Eakins' piece of work from that of most other nineteenth-century artists is his democratic and egalitarian definition of what constitutes achievement. Equally Elizabeth Johns has pointed out, heroism in Eakins' paintings (every bit in Whitman's poetry) is not confined to grand figures–clergymen, statesmen, and generals–simply is a quality that almost anyone, anywhere can display: surgeons, scientists, and inventors–even rowers, boxers, baseball players, and hunters.

Eakins' work is, as Johns understands, virtually a new kind of heroism, simply I would fence that what is most distinctive and important near Eakins' formulation of heroism is non the fact that it includes the common man, but rather the mutually supportive relationship it imagines to exist between consciousness and performance. As both the Gross and the Agnew portraits demonstrate, the essence of this distinctively American conception of heroism is its stunning equation of mental and practical power, as if at that place were no inherent obstacle in converting the one into the other. That daring leap of faith from mind to affair is the center and soul of the businesslike position and the deepest connection between Eakins' piece of work and pragmatic philosophy.

"American heroism," for Eakins as for James and Emerson, is precisely the ability of the individual to express his consciousness in worldly actions and events. To depict that transaction between inner and outer realms, Emerson invented the concept of "the heroic heed"–a term which signifies a state of composite thought and action in which the "thinking" and the "doing" are i (a concept which James borrowed verbatim from Emerson). Information technology would not exist too much to say that this belief that that the individual can perform his imagination in the world was the American dream: It was the vision that sure Romantic ethics of originality, inventiveness, and freedom (which English language Romantics and German language Idealists were willing to allow remain states of consciousness) could exist expressed in the ordinary doings of everyday life. To put it most baldly: The American dream consisted of the belief that to take a free imagination is actually to be able to brand oneself free in society. As Emerson tantalizingly put it at several points in his writing, the mind was endowed with the capacity to "realize" itself.

Merely fifty-fifty Emerson seems slightly more than cautious near the relation of the imagination to worldly expression than Eakins. When Emerson concludes "Feel" with the stirring peroration that "the true romance which the earth exists to realize volition be the transformation of genius into applied ability," he at least has the prudence to call the ideal a "romance" and to locate information technology somewhere in the indefinite future (the place Emerson typically locates all of his ideals). Eakins puts the "realization of genius" in the hither and now. The subject area of nigh all of his work is the intimate connexion between ideas and acts, impulses and executions....

–Excerpted from Ray Carney, "When Heed is a Verb: Thomas Eakins and the Doing of Thinking," in Morris Dickstein (ed.) The Revival of Pragmatism: New Essays in Social Thought, Law, and Culture (Durham, NC: Duke University Printing, 1998), pp. 377�403.

The preceding material is a brief extract from Ray Carney's writing virtually American painting. To obtain the complete text of this slice or to read more than discussions of American fine art, idea, and civilisation by Prof. Carney, please consult any of the three following books: American Vision (Cambridge University Press); Morris Dickstein, ed. The Revival of Pragmatism: New Essays on Social Idea, Law, and Culture (Knuckles University Printing); and Townsend Ludington, ed. A Modernistic Mosaic: Art and Modernism in the U.s.a. (Academy of North Carolina Press). Information about how to obtain these books is bachelor by clicking here.

Source: https://people.bu.edu/rcarney/ampaintings/gross.shtml

0 Response to "what is the name of eakins painting that is similar to the gross clinic? in what ways is it similar?"

Post a Comment